What do EFL learners think about working with mobile devices in the classroom? Does it make them more motivated? Do they participate more in class? Does it improve their English? Is there evidence for any affective improvements?

This blog post describes the findings of learner surveys on this, as part of a research project for The International Research Foundation in English Language Education (TIRF).

Health warning

- The tone of this blog post is a little more academic than usual. This is because it is to be read in tandem with the related TIRF paper on mobile task design and sequencing (due to be published online later this year).

- I make no claims at all for the generalisability or validity of this data. I have a long list of Caveats at the end of this post. But for me the surveys threw up some interesting – albeit anecdotal – data about learner perceptions and affective factors in the use of mobile devices. It certainly provided me with some food for thought. It may provide some for you too.

Who were the learners?

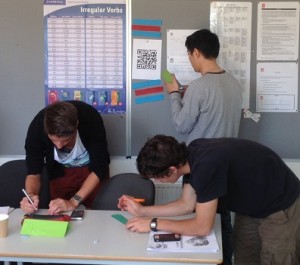

The project had students using their mobile devices to carry out communicative language learning tasks (we also used a course book). It was carried out with two consecutive small groups of international EFL learners studying at a private language school in the UK, over a period of two weeks in July 2013.

- The first group (week 1) were post-beginner level learners (A1+ level) with a total of 12 learners. The majority were Arabic speakers, with one Chinese speaker, and one Russian speaker. Half the class were adolescents (16 years old), with adult learners ranging from 20-45 years of age.

- The second group were of low intermediate level (B1) with a mix of nationalities among the 8 learners (Kuwaiti, Italian, Brazilian, Turkish, Argentinian and Chinese), and ages ranged from 16-27 years old.

- Each group attended three hours of class with me in the mornings, and another hour and half in the afternoon with another teacher.

What mobile devices did they use?

A BYOD (bring your own device) approach was chosen because the likelihood of most – if not all – learners owning smart phones or tablet computers was very high. This proved to be the case, with all learners in both groups owning smart phones (iOS, Android and Blackberry, with a majority of iPhone owners), and one tablet owner. Private language schools in the UK tend to attract students who can afford these devices, with professional adults attending, and adolescent learners coming from relatively wealthy backgrounds.

The initial class survey

In the first class of the week, both groups completed an online survey designed to check what learning experiences they may already have had using mobile devices, what devices and connectivity they had with them in the UK, and to gauge their attitudes to the idea of working with their devices during the coming week. In terms of attitudes and experience, the results of this initial survey were very similar for both groups:

- All the learners regularly used bilingual dictionary or translator apps on their mobile phones in class. None of the learners had ever used their mobile phones for any other language related activities.

- All of the learners in both groups agreed that using mobile devices could help them improve their English, and that they would like to find out more ways to do so both in and out of class. Although the learners had clearly not had any experience of this in the past, this showed that 100% of learners in both groups were positively disposed towards trying out mobile-based learning activities.

The end of week survey

An end of week survey was given only to the intermediate group, on the Friday of week 2. The survey contained questions focusing on the use of mobile devices, including whether they enjoyed using their devices overall, whether they found it useful, and soliciting comments/feedback on individual activities carried out in class.

It was decided not to administer the survey to the post-beginner week 1 group for a number of reasons:

- Their very low language proficiency meant that beyond yes/no, agree/disagree statements, it was difficult to get more detailed information from them on their experiences with mobile devices.

- In addition, 8 of the 12 learners left halfway through the morning class on the final Friday in order to attend the local mosque, so time was very limited in this final class.

- However, I did carry out one-to-one end of week tutorials with each of the beginner learners individually, and they all expressed (in limited language) that they had enjoyed using the devices, using words such as ‘like very much’, ‘new’, ‘different’, ‘interesting’, and expressing a desire to continue using their devices in subsequent weeks.

What did the learners say?

Here’s a downloadable PDF Survey Summary for the intermediate week 2 group. It shows:

- The majority of the class enjoyed using mobile devices (questions 3,7,8,9,17), and would like to continue to do so in the future (question 11). The majority also felt that using their mobile devices had improved their English (question 8), and their mobile literacy (see question 9) by familiarising them with new apps such as Chirp, Audioboo, Woices, and new mobile-related concepts such as QR codes – the latter were new to everyone in both groups.

But probably the most interesting thing this survey shows is:

- One learner clearly felt that there were few benefits to the mobile tasks, with comments such as ‘useless’ and ‘it doesn’t work’. This learner was reluctant to take part in any class communicative activities, either with me or with previous teachers, and preferred very structured written grammar practice activities in class. This is related to personal learning style and preferences, and expectations/beliefs about learning; it is also highlights the need for discussions about the benefits of not only using mobile devices, but of the communicative approach in general, for some learners.

Other survey findings worth highlighting address two typical BYOD teacher concerns:

- Question 13 explored the learners’ perceptions of an issue that often worries teachers: that in a BYOD approach, teachers need to understand how every mobile device in the room works, and need to be able to provide technical support for learners. Question 14 explores another concern: that a BYOD approach can only work if everyone has the same devices. The learners’ responses do seem to give some credence to both concerns. The majority of learners (6 out of 7) felt that the teacher should be familiar with the technology. On the issue of everyone needing the same device, the class was split, with a slight majority (4 out of 7) feeling that this was not that necessary.

Caveats: What are the limitations?

The questions posed at the beginning of this blog post are clearly large questions for a very small study. So here are the caveats:

- The timeframe for this study was very limited: one week with each group was not long enough to get the learners accustomed to using their devices, or to explore a wider range of mobile-based tasks. A longer timeframe – for example across a term, or even an entire school year – would make a more robust study.

- The scope of this study was limited: only two small groups of learners at fairly low levels of proficiency, were involved. A greater number of students with a range of levels of proficiency would make a more robust study.

- The study context of the study was limited: a multilingual group of relatively wealthy students in an immersion context (UK). Studies carried out in a number of monolingual contexts would be interesting for the purposes of comparison.

- The educational context of the study was limited: I was a single teacher trying out an ad hoc BYOD approach. Working as part of a team of teachers within an institution-wide implementation plan would ensure students could continue using their devices after I left, hopefully in a pedagogically sound manner.

- Not all students had 3G connections, or access to Wi-Fi at home, so mobile-based tasks that required connectivity had to be limited to the school and grounds. This meant that potentially interesting mobile-based out of class activities (e.g. using geo-location) could not be explored.

- Whether our week with mobile devices really improved the learners’ English is simply not possible to prove. Even with more time at our disposal, so many factors are involved in second language acquisition, that such a generalised question is problematic. But the learners perceived that their English had improved, and this is a positive affective outcome.

What’s the conclusion?

Is there evidence for any affective improvements from the use of mobile devices?

- The responses to the end of week survey by the intermediate week 2 group (apart from the one learner already mentioned) do seem to bear this out, with increased motivation and class participation noticeable during several of the mobile tasks.

- Increased motivation and participation were equally true of the post-beginner week 1 group where wholesale enthusiasm was noticeable, especially with the QR code tasks described here and here.

- The reluctant learner who gave consistently negative written feedback is important. Resistance or rejection of learning with mobile devices points to a need for careful planning and a far more staged approach with some learners. Starting on more familiar ground (e.g. with behaviourist language apps for homework), plus learner training and discussion might be more effective with some groups, rather than the ‘deep end’ approach taken in this project.

But these conclusions can only be applied to these learners, in this context. How about running your own classroom research project to find out what your learners think?

Please feel free to leave me a comment with your thoughts. Do your own experiences with mobile devices reflect my findings, for example?

Nicky Hockly

The Consultants-E

August 2013

Blog posts for my TIRF Research Project: